Black Art Activism

As the new year rolls around, the world seems to be taking a breath of fresh air. In 2021 there will be major political shifts, and (hopefully) progress on curing the coronavirus. In 2021, we are supposed to leave all the fighting and corruption and dying behind, right? While this is an enthusiastic approach, it is also unrealistic. There has been one event in 2020 that should continue into the new year: protesting for civil and equal rights. The anger our country felt for the injustices people of color are facing has lost its traction. For a few months, the rest of the country got a wake-up call to the racism that is still alive in our world, but our privilege has allowed us to be distracted by other things. People who aren’t daily affected by social injustice have lost interest and assumed that, because we protested a little, the problem went away. However, people of color weren’t allowed to ignore the problem. They are still fighting for their rights. Some of my favorite expressions of such protest are displayed through depictions of black culture in art.

Art has an interesting way of expressing hidden truths. To the untrained eye, art is just pretty pictures of objects or ideas. It isn’t until you look deeper at the choices the artist made when creating the piece and at the explanation of why the piece was made in the first place that you can truly understand the artwork. Art is never random, it always has a purpose. This is why black art has been swept under the rug. Their stories have been deemed unimportant and unrelatable to white people – which is partially true. White people can’t even begin to relate to the modern-day struggles of a black person or their ancestor’s history. But just because they have a different side of the story, doesn’t mean they need any less time in the spotlight.

This is my spotlight on a few of my favorite black artists.

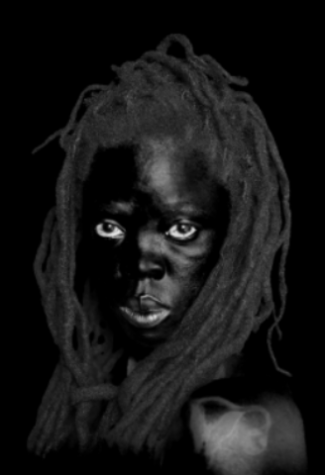

Zanele Muholi was born and raised in Umlazi, South Africa and now lives and works in Johannesburg. Their work focuses on not only the rights Africans still have to fight for 27 years after apartheid (a political system of racial segregation that was prominent in South Africa until around the 1990s) was lifted, but also on the rights that black LGBTQ+ members are fighting for. Muholi photographs portraits of people from the LGBTQ+ community to highlight their importance not

only in their own community but in the world. They also take portraits of South Africans who are victims of curative rape* and other hate crimes against the LGBTQ+ community. But their work doesn’t stop there. The subjects of the pictures are shown changing over the years in multiple part photographs as they find more of their identity. The most astonishing part of Muholi’s work for me personally is the way their self-portraits look directly into the camera, forcing the viewer to make eye contact and analyze the feeling and meaning behind their expression. Their work is unapologetic and projects strength.

Most of Muholi’s work is done in black and white, but when they photograph drag queens or beauty contest contestants, the piece is done in vibrant colors. Muholi shows the subject as magnificently proud of their identity and beauty. Drag queens not only wear modern style clothes but also native articles of clothing that are culturally meant for the opposite sex. This makes a statement against the prejudice in Africa that transgender and homosexuality aren’t for black people.

*Curative rape – a hate crime in which the victim is raped in order to convert them to heterosexuality

Nikkolas Smith has a range of different subjects in his pieces but they all share a common goal: to start a conversation about racial injustice in America.

His work is amazingly diverse, ranging from pop culture to abstract painted portraits, to the theme parks

he used to design at Walt Disney Imagineering. He also has done some work in the film industry by creating movie posters and helping to illustrate film, most notably work for the movie Black Panther. Recently he has focused more activism through political pop art pieces as well as illustrating and writing children’s books featuring black children. Born in Houston, Texas, Smith has worked hard to place people of color in important roles typically played by white people in America. Pieces such as The Obama Incredibles!, and Lemonade changes classic movie characters to pictures of people of color. Smith’s ability to push his way into the literal spotlight (usually held by white artists) through his activism artwork shows the lengths of his natural talent and imagination.

Adrian Brandon’s method of expressing racial injustice in America is by far my favorite. He begins by outlining the face of a black person who has died due to racially motivated violence. Brandon does research on each of his subjects

to find their life story and specifically their age. Each year of the person’s life counts for one minute of coloring, so the subject’s age determines how long Brandon will color in the face. The viewer is left with a partially completed piece symbolizing a stolen life. The time that was taken away from them is represented in the blank spots left on the face. For example, Aiyana Stanley-Jones (right) was just 7 years old when she died, so Brandon was only able to color for 7 minutes. Brandon shows a glimpse of the beauty the person could have been having, had they lived their entire life.

to find their life story and specifically their age. Each year of the person’s life counts for one minute of coloring, so the subject’s age determines how long Brandon will color in the face. The viewer is left with a partially completed piece symbolizing a stolen life. The time that was taken away from them is represented in the blank spots left on the face. For example, Aiyana Stanley-Jones (right) was just 7 years old when she died, so Brandon was only able to color for 7 minutes. Brandon shows a glimpse of the beauty the person could have been having, had they lived their entire life.

Another impactful series that Brandon does is his durag series. Brandon digitally paints pictures of black people wearing durags in everyday life. These pieces depict the back of the durag being extended and flowing out behind the figures as if it were a superhero cape. The subjects always look powerful and brilliant, sometimes with a fist up in the air like they are flying into the sky.

Another impactful series that Brandon does is his durag series. Brandon digitally paints pictures of black people wearing durags in everyday life. These pieces depict the back of the durag being extended and flowing out behind the figures as if it were a superhero cape. The subjects always look powerful and brilliant, sometimes with a fist up in the air like they are flying into the sky.

Each of these artist’s individual stories, as well as the community they represent, is important. We must all collectively fight to allow equal opportunities that aren’t dependent on skin color. If more artists like the ones above are allowed to share their work on a larger and more open-minded scale, then I believe that we will be even closer to equality.

As someone who isn’t a person of color, I don’t think I can fully describe what these pieces mean to the black community and to the artists themselves. Please check out two videos about Adrian Brandon’s art and Zanele Muholi’s art that do it much better!

Brandon’s – https://youtu.be/SnEFHZ-nGrM

Muholi’s – https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/zanele-muholi-art-21-1357777