The Role of Gender in Leadership on the Global Stage

On a global level, it is no secret women make up a limited number of foreign policy leaders. Women run for office at a rate far below that of men, and despite substantial national and international measures that have been taken towards gender equality, egregious gender inequality still exists globally. HuffPost reported in 2012 that “only four out of over 135 nations have achieved gender equality including Costa Rica, Cuba, Sweden, and Norway….Measures of gender equality include access to basic education, health and life expectancy, equality of economic opportunity, and political empowerment” (Kamrany). They further write that, “although there have been evident progresses, many alarming issues regarding gender discrimination still prevail today; therefore, total gender equality must be made a global priority as a fundamental step in both human development and economic progress” (Kamrany, 2012). Understanding the role and impact of gender majorities in international relations, it is clear that governments and businesses across the globe must actively work against the barriers to female representation in politics and international security through concrete policy, business incentives, and brave global leadership that recognizes the role of leading women in both economic and social development.

Obama meets with the national security team on Iraq in the Situation Room of the White House in Washington / Reuters

Barriers Women Face Across the Globe

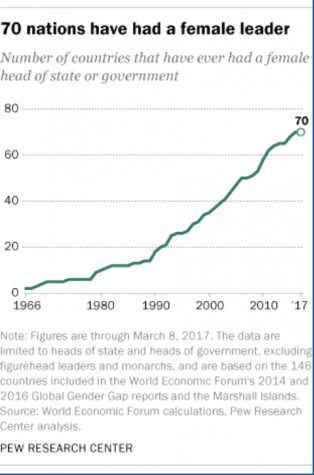

The number of female leaders across the globe has slowly grown since 1964; however, they remain a small group on the international stage. According to A.W. Geiger of Pew Research in 2017, women represent fewer than 10% of 193 UN member states, make up a minuscule percentage of global leaders and heads of state, and seen in (Figure 1), while global numbers of female leader have steadily increased each decade since 1966, in 2019 only 70 nations out of 195 were headed by women, and ⅗ of those nations were in Europe.

Figure 1

Many believe that the reason behind the lack of women in positions of power is because they are not afforded opportunities for leadership positions later in their careers, as Micah Zenko writes in The Atlantic in 2012. He cites freelance writer Diana Wueger, who suggests there are even deeper roots to global female underrepresentation, and that often in the debate over the underrepresentation of women in foreign policy and national security “we’re focused on the wrong point in the career trajectory. Rather than bemoaning the lack of women at the top, we should be asking whether women at the start of their careers are being offered the assignments, experiences, and opportunities that lead to later success.” She further explains the gap in the types of tasks women and men are assigned early in their careers, that “intentionally or not, women tend to be given more administrative or support work rather than policy or research work; path dependence takes over from there.” (Zenko, 2012).

In June of 2019, Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman posted a Harvard Business Review article about new social research into the leadership capabilities of both men and women, Research: Women Score Higher Than Men in Most Leadership Skills. They reported that, while men hold 95.1% of CEO positions in Fortune 500 companies, make up over 70% of the U.S Congress, have continuously held offices of presidency, operate the majority of state & global leadership, and consistently been the majority cohort in the U.S. Senate and the Supreme Court, women are measurably just as good, if not better, leaders than men.

In fact, in 84% of the categories they tested, women actually scored higher than their male counterparts in the most frequently tested leadership areas. Most specifically, women in the study were found to be rated as “excelling in taking initiative, acting with resilience, practicing self-development, driving for results, and displaying high integrity and honesty..”, while the mere two (out of nineteen) capabilities men were rated higher on were “developing strategic perspectives” and “technical or professional expertise” (Zenger, 2019).

If we understand the inherent value women bring to work environments and decision-making bodies, it is valid to ask why have the numbers of women in business and politics not soared or at least steadily increased? Why, if women are so equipped to lead, at least equally equipped as men, do they not make up even 10% of top leadership positions in the most influential global businesses? Harvard Business suggests that it may be in part due to the “broad, cultural biases against women,” and that these long-held belief systems often die slowly (Zenger, 2019). Further, they suggest that young women, specifically those under 25, are far more likely to assume that they’re not qualified for a position, while a man with their exact credentials will assume that he can learn what he’s missing and succeed in the position. This “confidence gap” was measured by Harvard Business as well, and they report that it is not until around age 40 that men and women have similar scores in terms of self-rated self-confidence in their marketable abilities (Zenger, 2019).

Mary Barro, CEO of General Motors, reports that a key in solving the global gender gap is putting more women in charge. Data from The World Economic Forum in 2017 shows “when women are better represented in leadership roles, more women are hired across the board” and that this “holds true even when considering disparities in the size of female talent pools across industries.” Author Sue Duke writes that it’s clear the percentage of women in leadership positions is growing too slowly despite the fact these positions are necessary to close the overall economic opportunity gap for women. She writes, “it is clear that we need to increase and accelerate female representation at the highest level,” simply because the way to get more women into long-term leadership positions is “by already having women in leadership” (Duke, 2017). Without consciously incentivizing businesses to have quotas for the number of women in high-level administrative or managerial positions, the gender gap will continue to leave more generations of young women without role-models in politics and business.

Unfortunately, male majorities in leading bodies often discourage women from running for office or for competitive and high-paying jobs & promotions. In Carolin Scheidele’s 2019 paper on “Male Majority, Female Majority, or Gender Diversity in Organizations: How…Proportions Affect Gender Stereotyping and Women Leaders’ Well-Being,” the point is made that “not only a male majorit[ies], but also a female majorit[ies]” in the workplace “[have] negative consequences, because gender becomes salient in both cases…[but] empirical research on work environments with female majorities at the top of organizations is scarce.” Gender, while it is disregarded by most realist IR theories, plays a key role in the execution and the impacts of foreign policy.

When Women Lead

After observing women in work environments and conducting in-depth analysis, Harvard Business Review concluded that women make “highly competent leaders, according to those who work most closely with them,” and that what’s holding them back is “not lack of capability, but a dearth of opportunity” (Zenger, 2019). While it is most definitely a liberal approach backed by feminist ideals, the only way for gender dynamics to shift is when business and policy consciously change their perspectives and hiring models to invite women to the table, to encourage them to get promotions early on in their careers, and to be unapologetically sure in their capabilities to lead, make change, and stand equal to men in both the board room & in their checkbooks.

Politicians across the globe are calling for international leadership to tackle the issues of deep-rooted gender inequality. In December of 2011, Secretary Clinton spoke to the critical need for the inclusion & mobilization of women abroad to U.S. national interests, due to the fact when women lead across the globe they “raise issues like human rights, citizen security, justice, employment, health care” and “speak on behalf of other marginalized groups and across cultural and sectarian divides” (Zenko, 2012). Gender discrimination, on a national level, poses threats to economic growth as it prevents counties from reaching their maximum productivity potential. “Although women constitute 40% of the global workforce, there are still many who are unpaid family workers in the informal sector….paid much below that of male workers, despite being equally capable and skilled,” and their status & promotion is “limited to middle or below ranks” (Kamrany, 2012). Women are laid off pre-retirement age more frequently, have limited educational opportunities, and typically “run smaller farms & less profitable enterprises” (Kamrany, 2012). When women are kept out of the paid workforce or stay at minimum-wage and low-level positions, many countries experience loss of productivity that’s at least “25% due to gender discrimination” alone (Kamrany, 2012). Gender equality in leadership is not necessary to the functioning of most nation-states, yet it does perpetuate existing inequalities, eliminate balanced viewpoints, and diminish the role of women in society.

Liberalism, Feminism, and International Theory

Gender is not always deeply examined in the traditional studies of international relations; realism’s focus on power studies and war offers few lenses through which to analyze the role & impact of women on the international stage. Because of this, I turn to liberalism and feminism to back my claims. Therese Etten writes in 2014 that feminism is the approach that’s contributed the most to the study of gender in IR theory. She writes that realists often focus on issues of war and national security far before considering the gender relationships that are often framed as irrelevant in conventional realist theories.

In Alison Pullen’s paper Feminist Ethics and Women Leaders: From Difference to Intercorporeality in 2020: “If women are understood only in relation to men rather than on their own terms, women will continue to be subordinate in leadership practice and thought.” She furthers that women today are “scrutinized on issues…ranging their suitability and capabilities to perform leadership roles, the advantages and disadvantages that women bring to leadership, and the structural inequalities they suffer from.” Pullen further argues that women “should not be evaluated against men, but rather, as a separate individual,” as female leaders today are persistently “scrutinized and disadvantaged by systemic discrimination in theory and practice.” (2020)

“Feminism has long shown us that changing the culture which frames our subjectivity and our negation is a necessity for emancipation. Nevertheless, the question remains: How can women act?” (Pullen, 2020).

The impact of Gender Majoriaties on International Relations

In the words of the National Democratic Institute’s (NDI) Chairman, Madeleine Albright, women in power “can be counted on to raise issues that others overlook, to support ideas that others oppose, and to seek an end to abuses that others accept.” On a global scale, gender majorities affect the ways in which countries express themselves and the messages they send to their population and the international community. Anne Tickner insightfully reflects that she has found that “while many…male students seem quite comfortable with the discourse of war and weaponry in my introductory course on international relations, a semester has never passed without some of my female students expressing privately that they fear they will not do well in this course because it does not seem to be “their subject.” In trying to reassure these women that they can be successful, I have often paused to reflect on whether this is “my subject.” Frequently, I have been the only woman on professional panels in my field, and I am disappointed that I cannot find more women theorists of international relations to assign to my students” (Tickner, 1992, p. 2).

On the subject of representation, the celebrated international relations theorist furthers that “women have rarely been portrayed as actors on the stage of international politics” (Tickner, 1992, p.2). She most eloquently states how the history of foreign and military policy-making having been largely conducted by men, “the discipline that analyzes these activities is bound to be primarily about men and masculinity,” she writes that “in most fields of knowledge we have become accustomed to equating what is human with what is masculine. Nowhere is this more true than in international relations,” a discipline that, while it has, for the most part, resisted the introduction of gender into its discourse, “bases its assumptions and explanations almost entirely on the activities and experiences of men” (Tickner, 1992, p.8).

Continued Challenges to Equal Representation & Recent Successes

Despite global systemic challenges and barriers to female representation in business leadership and politics, there remains hope for a more equally represented global system. Women-led initiatives are doing the groundwork for future generations. Organizations like Heifer International, The National Organization for Women, and The Association for Women’s Rights in Development all show promising progress for women in positions of power. Another testament to slow yet continuous growth is the 2020 elections in the United States, which were groundbreaking for women; the highest proportion of women in Congress than ever before elected to serve with 27% of the House and 25% of the Senate identifying as female (Congressional Research Service, 2020). Constantly, women of all ages, races, and backgrounds are pushing the boundaries of what they can accomplish, stretching the limits of expectation for all generations to come.

U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) speaks as Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), Ilhan Omar (D-MN), and Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) listen during a press conference at the U.S. Capitol on July 15, 2019, in Washington, DC

Looking forward: Creating a World with Leading Models for All People

Research from The Huffington Post suggests that there are tactful ways to eradicate the gender gap in political representation. Quotas for the number of male versus female politicians have increased female leadership in India, and after surveying over 400 villages a report suggests that “results were astounding…in areas with long-serving female leaders in local government, the gender gap in teen education goals disappeared, due to the fact that girls had set higher goals for themselves. Parents were also 25% more likely to report having more ambitious education goals for their daughters, significantly narrowing the gender gap.” Clearly, there is an impact on young women today when women show up as their politicians, are expected to uphold high educational standards, and feel as though they can be brave leaders who are necessary for a successful global system.