Removed Pews Of Kennebunk Church Reveal A History Of Slavery In Maine

It is widely assumed that slavery was abolished throughout the Union as early as 1780, right after the United States gained its independence from England. However, that wasn’t the case.

Recently, Reverend Lara Campell of the Unitarian Universalist Church, has uncovered historical documents that provide evidence to the notion that there was in fact slavery in Kennebunk, dating back to as late as 1805.

Campbell’s interest piqued when she discovered a peculiar outline of pews that had been removed in the belfry of the church.

She decided to dig into the archives of the church to try and uncover the origin of what she was looking at, and in doing so, found these documents.

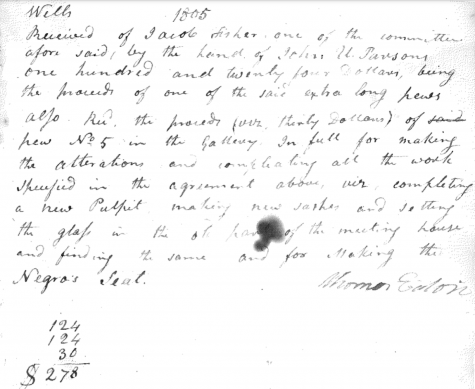

These documents highlight the process and payment of the building of the Unitarian Universalist Church. Within the writing, architect Thomas Eaton states the need to “build a suitable place in the belfry, of three or more seats, for the people of Colour to sit.”

Campbell was quite shocked when she found these papers, as they deliver direct evidence to the mysterious outline of pews being built for the black community of Kennebunk.

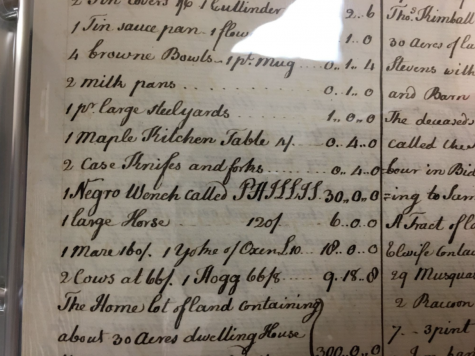

She then stumbled upon a parchment that inventoried the net value of the household. Near the bottom, the document mentions that one of the items of the house was “1 negro wench named Phillis” who was worth $30. Campbell’s research has uncovered that there were indeed slaves in Kennebunk, and the removed pews in the Unitarian Universalist Church were originally built for the enslaved population of Kennebunk.

What does this mean?

It’s a lot to process the idea that there were slaves in New England as late as the early 1800s, especially when many students learned otherwise in their history textbooks. What does this actually imply? Well, this discovery may just be more proof that history shouldn’t be taken at face value, but should be researched and questioned in order to gain a deeper and more true understanding of what has transpired throughout history, specifically North America.

How do we proceed?

The last and perhaps most important question is: How do we proceed? The town of Kennebunk has yet to recognize any of this history, and there have been discussions about what can and should be done in order to honor these unpronounced members of Kennebunk’s history. In Kennebunk High School’s Race in America class, students discussed their opinions on what should be done. The most prominent ideas were placing plaques of memorial on the historical houses where these slaves lived in order to pay respects or creating an exhibit in Kennebunk’s Brick Store Museum. However, it is up to the town to decide if anything will be done.

Allan Davis • Jul 16, 2024 at 8:58 PM

I live in kennebunk, presently. I was a member of Dane Street Church, and I have always been suspicious about this kind of issue in the town. I do understand why there’s only several families of colour in this town. I think it’s commendable that this issue is not being ignored.