Eighteen seniors are graduating from the Kennebunk High School theater program, so it was only fitting to go out with a bang. Well known for its outstandingly large cast, the school play this year was Spamalot, a musical adaptation of the comedy Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which is in turn a satirical dramatization of King Arthur and the search for the Holy Grail.

Many of the students in the KHS theater are queer. This fact influences the decisions in casting, as well as the way the cast interacts with each other. The inclusion of a queer population allows for new interpretations of characters, as well as a better understanding of the students as actors and a more familiar connection between them due to their shared experiences.

King Arthur, the leading role, is known for being a strangely paragonal, masculine figure in English history. Who else to play him except for a transgender man? Crow Lowry, a recently adapting baritone, was King Arthur. The once broad, muscled figure has been reimagined at a stature of 5 ‘3″. Other roles include the ‘homicidally brave’ Sir Lancelot, played by Cassie Midgley, and Sir Robin, the ‘not-quite-so-brave-as-Sir-Lancelot’, played by Quinn Downing. Both actors are significantly taller than Crow, with Quinn reaching a solid foot above Crow’s stature. On stage this adds another comical level to the scene, where the king must look up at his subjects.

From left to right: Patsy, Bedevere, Galahad, Arthur, Lancelot, and Robin

Photo by Mr. Holmes

Many bold choices were made in the show to the great success of the production. Lancelot du Lac, famous for his love of Guinevere, is a closeted gay man in Spamalot, though he was depicted by a heterosexual woman. It was an interesting choice, and Midgley herself said of the role, “It was a little difficult because I didn’t directly relate, but honestly I didn’t think of portraying a ‘gay man’, I just portrayed the character I found him as: a guy who couldn’t be himself without a cover-up… eventually his walls came down and he could accept it and just love who he loves!!”

Alongside her were Quinn and Crow, both of whom are gay men who were there to guide her through her acting choices. “I think it was helpful to have some gay men to call upon and see how they relate,” Midgley stated, “it helped me get a stronger sense of the character and portray him better.”

By having these two to talk to, Midgley was helped in her development of Lancelot from being a flat stereotype to a developed character, making his song, “His Name is Lancelot,” a parody of a classic 70s disco bop, all the funnier.

Cassie Midgley as Sir Lancelot

Photo by Mrs. Pollard

Other characters, who appeared heterosexual in the show, were played by queer actors. Both Arthur and Guinevere, who share an on-stage kiss, were played by queer actors Lowry and Erin McNeilly, both of whom have their own boyfriends off-stage. The two of them have been friends for over a decade. Both of them were there for the other when they started grappling with their own queer identity. “It made it a lot easier for me,” Lowry says about the kiss, “knowing that it wouldn’t be muddled with things like feelings. We know each other, it wasn’t uncomfortable for me”.

The cast is composed of friends, those who have bonded both in school and out. Over two thirds of the cast identify as queer, which made for very trusting company. Quinn Downing, our Sir Robin, said this of the cast: “I feel good working in a cast of queer people, which makes theater feel like a safe space. I think there is definitely a desire between the queer people in theater to preserve our safe space.”

Theater is an intimate space filled with emotion. A large amount of theater is about vulnerability and connection, which makes for very deep and complex roles, but also means that actors must trust each other. Familiarity is a great start when creating trust, and familiarity can come from shared experiences, such as the queer experience. When you know you’re not alone, the world (and the stage) become far less terrifying. An actor can explore a character in a space without the fear of judgment when they are with friends.

The insertion of queer students allows for these new interpretations of the characters. Different influences and life experiences make characters, and you must enter a role with those ideas in mind. The queer experience, though not universal, diverges from the heteronorm, and creates a new foundation for a show to be built upon. New interpretations are happening in every production, no matter who is playing them, as that is the nature of acting. But the queer actor can add their own attitudes to a character a heterosexual audience is unfamiliar with. However, in order for this to happen, there must be an opportunity.

An actor must open up to other actors and to the audience in order to portray a role, and with the tentative attitude towards queer people, showing oneself can be frightening. This is how trust is integral to the new theater we’ve created. We must open up to new ideas and bond to create a better, stronger theatre space.

Avery Rossics (Patsy) and Crow Lowry (Arthur)

Acting, however, is only one half of a show. Behind the scenes are the techies, people who make the show happen. Techies are the creators of lights, sound, props, costumes, and sets. Techies literally create the physical space for actors to exist in. This means they are responsible for making a comfortable scene, and those responsible are also often queer.

For example, Lowry is not just King Arthur, but has been the costumer at the high school every year they’ve been here. “I’ve tried really hard to make myself approachable,” they said, “I need people to tell me if they’re uncomfortable in their costumes. I can’t help them if they don’t tell me.”

Lowry has experience with being uncomfortable in clothing, as they are transgender. “Clothing is so important to how people see you, and that extends to a character.” Lowry has played many roles, both on and off stage. It’s important to any actor that they get a costume they feel comfortable in- if they’re not comfortable, it becomes difficult to act. A transgender costumer knows this intimately, and they try their best to make sure everyone is comfortable. This results in a continuation of having queer people not just on stage, but visible on stage. Women in suits and men in blouses continue to rise in shows without being a punchline, but instead people existing.

Crow Lowry in the costume shop

Due to the nature of putting on a production, everyone is around each other for many hours every day. With days being up to nine hours, actors and techies spend a lot of time together. The queer folk in the theater bond and make the days and nights bearable. Painters squeeze in beside each other and make conversation about their lives, set construction techies haul wood together and chat, lighting and sound sit side by side and discuss anything and everything from podcasts, how to make a scene cohesive, to the worldbuilding of Star Wars, all while making sure everything runs on time. Camaraderie is high in the theater, and with an understanding of familiarity, the connection is only made tighter.

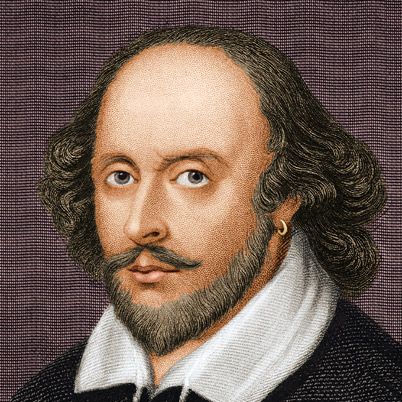

While it’s debated whether or not he was real, writings about King Arthur first started cropping up in the 9th century with the Historia Brittonum, and he was depicted as being alive around in the 6th century, winning the battle of Mons Badonicus in 516 and dying at the Battle of Camlann in 536. He was a magnificent and stern figure of pseudo-history. He is later depicted in Welsh mythology and is associated with Annwn, a place akin to the afterlife or ‘otherworld’.

This mysterious man with an otherworldly connection is reminiscent of the experience of queer people throughout history, especially in theater. In the eyes of the cis-hetero man, queer people take on a mythic quality, much like Arthur, and their existence throughout history is heavily debated. Often labeled as otherworldly, either good or bad, queer identities were and are treated as an ‘other’. The story of King Arthur, despite its glorification, is rather isolated and sad up until his gathering of the Knights of the Round Table, who appear in Galfridian texts.

The history of King Arthur can be divided into pre and post Galfridian texts, which were written in the 1130s. Pre-Galfridian texts described a single warrior facing off against otherworldly beasts to defend all of the British Isles alone. It was Geoffrey of Monmouth, a writer in 1138, who penned the new story of Arthur to include the characters that we know such as Guiennevere, Merlin, and of course, the Knights of the Round Table.